The Luddite fallacy

There seems to be a widespread belief that automation destroys jobs, makes most people poorer, increases income inequality, and ultimately hurts both the economy and society. This belief is not new. The Luddites were 19th-century textile workers who destroyed new machinery they perceived as a threat to their jobs. But it is perhaps surprising that after centuries of technological advancements, some still fall for the Luddite fallacy—the conviction that innovation has harmful effects on employment.

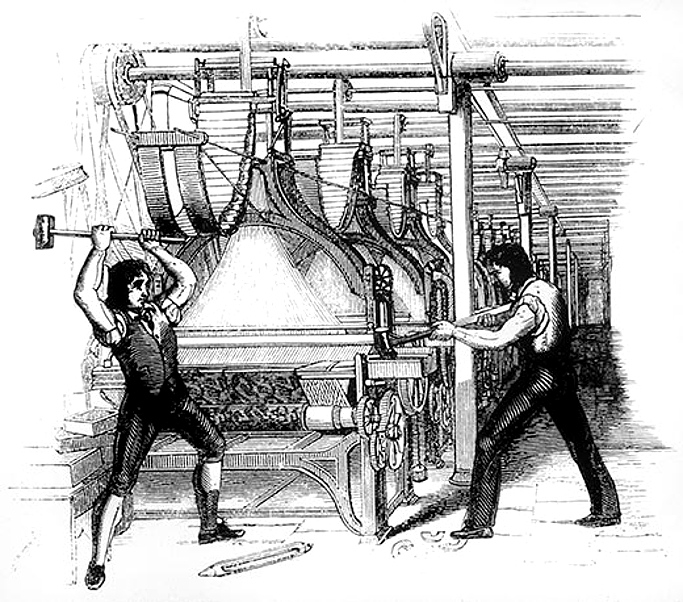

Machine breaking (1812)

Machine breaking (1812)

Today, with the help of inventions, we have more conveniences in our lives than ever before. Some were once luxuries that few could afford, like foreign food, but most are so incredible that our ancestors could not even dream of them, like airplanes, antibiotics, and satellite navigation. And although most jobs available a century ago no longer exist, other jobs were created, and most people live much more comfortable lives compared to back then.

The fallacy that automation hurts society is the result of an incomplete analysis: a conclusion based solely on the belief that the people whose work is automated lose their jobs. Missing all other consequences leads to a conclusion that does not correspond to reality. When analyzing all implications, it becomes clear that automation creates, not destroys value, doesn’t harm employment, and benefits everyone.

Over time, many people have explained this fallacy in eloquent terms. Below I am quoting the demonstration of Frédéric Bastiat, a French economist who lived in the 19th century. Even then, for him this process was very clear.

Harm Of False Premise

We need not be surprised at this. On a wrong road, inconsistency is inevitable; if it were not so, mankind would be sacrificed. A false principle never has been, and never will be, carried out to the end. Now for our demonstration, which shall not be a long one.

James B. had two francs which he had gained by two workmen; but it occurs to him, that an arrangement of ropes and weights might be made which would diminish the labour by half. Thus he obtains the same advantage, saves a franc, and discharges a workman.

He discharges a workman: this is that which is seen.

And seeing this only, it is said, “See how misery attends civilization; this is the way that liberty is fatal to equality. The human mind has made a conquest, and immediately a workman is cast into the gulf of pauperism. James B. may possibly employ the two workmen, but then he will give them only half their wages for they will compete with each other, and offer themselves at the lowest price. Thus the rich are always growing richer, and the poor, poorer. Society wants remodelling.” A very fine conclusion, and worthy of the preamble.

Happily, preamble and conclusion are both false, because, behind the half of the phenomenon which is seen, lies the other half which is not seen.

The franc saved by James B. is not seen, no more are the necessary effects of this saving. Since, in consequence of his invention, James B. spends only one franc on hand labour in the pursuit of a determined advantage, another franc remains to him. If, then, there is in the world a workman with unemployed arms, there is also in the world a capitalist with an unemployed franc. These two elements meet and combine, and it is as clear as daylight, that between the supply and demand of labour, and between the supply and demand of wages, the relation is in no way changed.

The invention and the workman paid with the first franc, now perform the work which was formerly accomplished by two workmen. The second workman, paid with the second franc, realizes a new kind of work.

What is the change, then, which has taken place? An additional national advantage has been gained; in other words, the invention is a gratuitous triumph - a gratuitous profit for mankind.

From the form which I have given to my demonstration, the following inference might be drawn: “It is the capitalist who reaps all the advantage from machinery. The working class, if it suffers only temporarily, never profits by it, since, by your own showing, they displace a portion of the national labour, without diminishing it, it is true, but also without increasing it.”

Who is the gainer by these additional advantages? First, it is true, the capitalist, the inventor; the first who succeeds in using the machine; and this is the reward of his genius and his courage. In this case, as we have just seen, he effects a saving upon the expense of production, which, in whatever way it may be spent (and it always is spent), employs exactly as many hands as the machine caused to be dismissed.

But soon competition obliges him to lower his prices in proportion to the saving itself; and then it is no longer the inventor who reaps the benefit of the invention - it is the purchaser of what is produced, the consumer, the public, including the workmen; in a word, mankind.

You can download a short book with Frédéric Bastiat’s essential texts for free here.

Automation benefits us all by creating value through increased productivity, making products less expensively, and freeing our time and resources for other useful endeavors, like doing medical research. But it can also cause a temporary inconvenience for the people whose work is automated. So a determined Luddite could still ask: are these temporary inconveniences worth it for the lasting benefits that we all gain?

The question of worthiness asks whether the efforts people made across time were worth it for getting us where we are now. It is for everyone to decide if they want to pursue such a question. In doing so, one needs to realize, though, that to oppose technological advancements means to reject all the past inventions that we benefit from today. And it doesn’t mean to reject them only for one’s self, but to advocate that everyone who is in favor of comfort should be forcefully prevented from achieving it.

For those who really put no value on comfort and prefer the harsh conditions of primitive life, changing jobs would not be an inconvenience, as they would instead retreat to the wilderness. It is not, however, from some remote cave that these moralists are preaching against innovation. In fact, they usually do so using the most innovative communication tools available. This makes their position either ignorant or hypocritical, and in any case contradictory.